The Wheel

This DD (Due Diligence) is going to be a little different.

Different because I’m not conducting deep research on a single stock I think is a great long-term hold. Instead, I’ll be doing surface-level DD on a handful of stocks that could make excellent Wheel strategy candidates.

By the end of this DD, you might learn a thing or two about options trading, and you’ll walk away with a viable, relatively safe, ready-to-go systematic trading strategy that can generate regular passive income, and maybe even make you feel like a genius while doing it.

Do you need to be an “options wizard” to trade the Wheel? Absolutely not. In fact, I’ll be writing this as if you have zero options trading experience. Options can be complicated, the price of an option is derived using some version of what’s called the BSM (Black–Scholes–Merton) option pricing model, which is actually a partial differential equation. All of that just to calculate what an option should be worth.

Then there are the Greeks, Not the Greeks who gave us philosophy and influenced Rome. These Greeks measure different variables of risk. In total, there are four first-order Greeks, three second-order Greeks, and six third-order Greeks.

But don’t worry, I’m only going to give you what you actually need to know to trade the Wheel. And I’ll explain it in a way a 10-year-old could understand. I’ve read the textbooks, the papers, and I’m doing the mathematics and statistics degree, so let me be your translator. My goal is to give you a clean, safe entry point into this strategy.

Why? Because in the world of options, there’s a lot of “know-it-alls” larping as gurus, and a lot of bad advice that can easily send you down the wrong path, one that could bankrupt you before you even realize what happened.

So if you already know a lot about options and find yourself asking, “Does this guy not know what Gamma is?” - trust me, I do. I’m just simplifying everything so that anyone, even someone pulled off the street, can understand it.

Here’s the structure of this DD:

- Explain how the Wheel strategy works (includes what you must know about options).

- Provide some light DD on a few solid Wheel candidates.

Don’t worry if you feel confused so far, everything will be broken down step by step.

Not a fan of reading? Watch my YouTube summary video that walks through this entire DD report:

Prologue

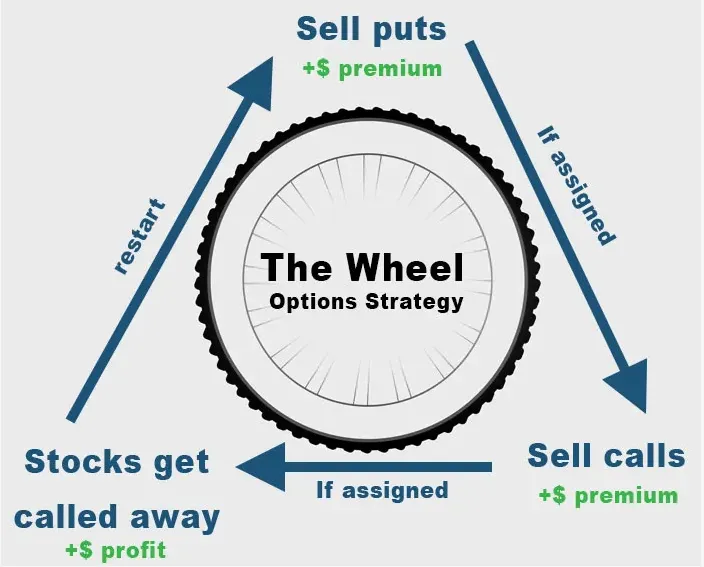

The wheel is this:

Basically, the Wheel is a systematic process: you start by selling a put contract, wait to get assigned, and once you own the shares (usually in blocks of 100), you sell covered calls against them. When those shares eventually get “called away” (sold at the strike price), you circle back to the beginning and repeat the process.

Let’s break it down into simple, easy-to-follow steps:

Step 1: Sell a put contract.

- You’re agreeing to buy 100 shares of a stock at a certain strike price if the option is exercised.

Step 2: Get assigned.

- If the stock closes below your strike price at expiration, you’ll be assigned 100 shares.

Step 3: Sell a call contract against those shares.

- Now that you own the shares, you sell a covered call to generate premium income.

Step 4: Your shares get called away.

- If the stock rises above the strike price, your shares will be sold at that strike.

Step 5: Repeat the cycle.

- Return to Step 1 and sell another put, continuing the wheels endless cycle.

Now let’s break each step down in detail. If you knew nothing about options before, this is where things will start to make sense.

Before we get into Step 1, we need to take a quick detour. To understand how the Wheel works, you first need to know what an option actually is, why options exist, and how they work.

What is an Option?

textbook definition:

An option is a contract that gives the buyer the right, but not the obligation, to buy (call option) or sell (put option) an underlying asset at a specified price (the strike price) within a specified period of time.

Street Definition

Say Stock ABC is trading at $100 per share.

Mike thinks that in two weeks, ABC will trade above $120. Sarah disagrees. So Sarah says to Mike:

“If you pay me $10, I’ll give you the right to buy 100 shares from me at $120 each, but only if the stock finishes above $120. If it doesn’t, I keep your $10.”

Mike thinks about it. Normally, to buy 100 shares of ABC, he’d have to put down $10,000 (100 × $100). But with this option trade, he only risks $10 instead of $10k, while still getting the potential upside if the stock rips past $120, because one option contract controls 100 shares.

Mike accepts the deal.

Two weeks later, stock ABC finishes at $119.99. Just a penny shy.

- Mike loses his $10 premium.

- Sarah keeps the $10 profit.

That’s an option in street terms: a small upfront payment for a chance at a bigger move, but if you’re wrong, you only lose what you paid.

Option FAQ's

Now that we’ve covered the basic definition, let’s break down the components of an option contract by answering some frequently asked questions:

What’s in the contract itself?

Each option contract represents 100 shares of the underlying stock. So, when you see an option price quoted on an exchange, that price is per share, and you must multiply it by 100 to find the total cost. For example, if an option is listed at $0.34, the contract would cost $34 (0.34 × 100).

What's a "Strike Price"?

The strike price is the agreed-upon price of the underlying stock written into the option contract. In simple terms, it’s the price you’re betting the stock will (or won’t) reach by the expiration date.

What’s an “Expiration Date”?

The expiration date is the deadline of the option contract, the last date the option is valid. By this date, the stock must reach (or move past) the strike price for the option to have value. After the expiration date, the option simply expires and becomes worthless.

Do I have to hold until expiration?

No. You can sell the option contract at any time before expiration. Each option trades much like a stock: you’ll see a bid/ask spread, price movements, and even a chart on your brokerage platform. In other words, every option contract can be bought and sold in the market just like shares of stock.

Can I get exercised early?

Yes, but only on U.S. options (which is what we’ll be trading). U.S. options follow the American-style exercise rules, meaning the option buyer can choose to exercise their contract at any time before expiration. However, this is very unlikely in most cases.

(For context, I’ve personally traded thousands of option contracts, both long and short, and have never had one exercised early on me.)

Okay, lets park this for a second and get into step 1 of the wheel strategy, which is selling a put contract.

What does ITM, ATM, and OTM mean?

- ITM (In the Money): The option already has value if exercised.

- Example: A call with a strike of $90 when the stock is $100 (you can buy at $90, sell at $100).

- ATM (At the Money): The strike price is about the same as the stock price.

- Example: Stock is $100, strike is $100.

- OTM (Out of the Money): The option has no intrinsic value yet, it only has value if the stock moves.

- Example: A call with a $110 strike when the stock is $100.

What is "Intrinsic and Extrinsic Value"?

Intrinsic Value

- This is the real, tangible value of an option if it were exercised right now.

- For a call option, intrinsic value = stock price − strike price (if positive).

- For a put option, intrinsic value = strike price − stock price (if positive).

- If the option is out of the money, it has no intrinsic value, it’s entirely based on potential.

Extrinsic Value

- Also called “time value.”

- This is the additional value an option has because there’s still time left until expiration, time for the stock to move in your favour.

- Extrinsic value is driven by time remaining and implied volatility (IV).

- As time passes (Theta decay), extrinsic value shrinks to zero by expiration.

Step 1: Selling a put contract

First off, what's a put contract?

A put contract is an options contract that gives the buyer the right (but not the obligation) to sell 100 shares of a stock at a set price (the strike price) before the expiration date. When you sell a put, you’re taking the other side of that trade, agreeing to buy 100 shares at the strike price if the buyer chooses to exercise the option.

So basically, if you buy a put, it means you want the stock to go down. Why? Because if the price falls below your strike price, you have the right to sell 100 shares at the strike price. You could then buy those same shares back on the open market at the lower price, locking in the difference as profit.

Understandably, this can sound confusing, because it ties into the concept of shorting shares (a whole separate topic on its own). For simplicity, just remember this: when you buy a put, you’re betting the stock price will go down. If you exercise that contract, you’d effectively end up being short 100 shares.

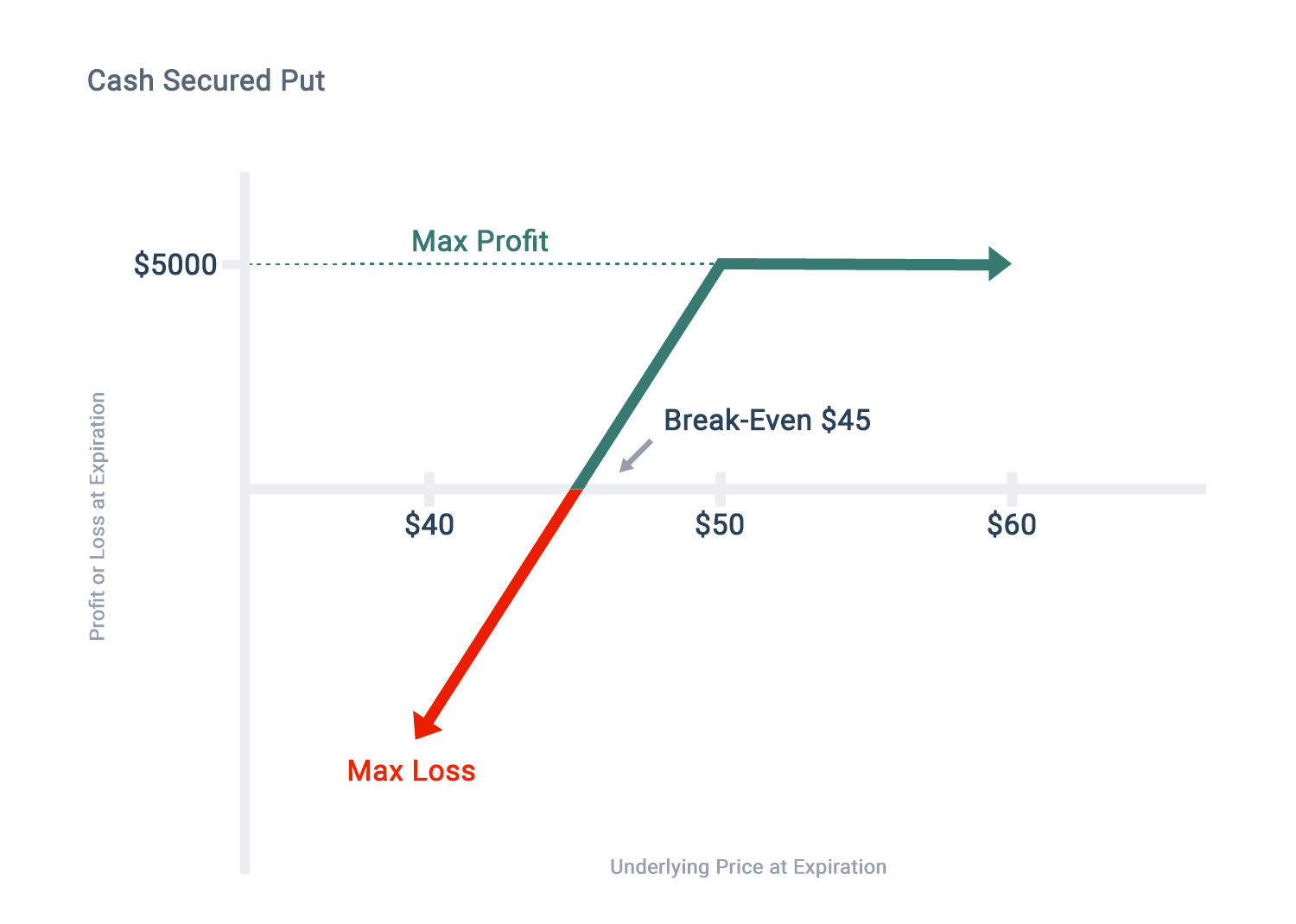

Now, if you can buy a contract, that must mean someone is selling it, right? Yup, exactly. Selling a put contract is effectively the opposite of buying one. If you sell a put, you’re betting the stock will stay the same or go up. Why? Because if the stock falls below the agreed-upon strike price, you’ll have to honour the contract at expiration, which means you must buy the stock at the strike price, even though the market price is lower. That difference is your loss.

However, if the stock stays above the strike price, nothing happens, and you keep 100% of the money that the buyer paid you for the contract. This payment is called the premium.

The premium is essentially what we’re after here. Think of it as “farming premium”, that’s the goal, and we want as much of it as possible. Premium values can move up or down depending on several factors, but when selling put contracts there are three key variables to focus on: Delta, Theta, and IV (Implied Volatility).

I’ll explain what these three variables are, but don’t worry if it still feels confusing. I’m going to give you the exact numbers to use for each one anyway, and those numbers won’t change, because we want to set up this strategy in a systematic, repeatable way.

Delta:

Delta measures how much an option’s price is expected to change when the stock price moves by $1.

- A call option with a delta of 0.40 will gain about $0.40 in value if the stock rises $1, and lose about $0.40 if the stock drops $1.

- A put option has a negative delta (e.g., –0.40), meaning the option gains value when the stock goes down, and loses value when it goes up.

Honestly, this it's cool to know, but kind of useless for us. For our purposes, you don’t need to dive into all the math, just know this:

- Delta is also used as a rough estimate of the probability that the option will finish in the money.

- For example, a 0.30 delta put means about a 30% chance of assignment, and a 70% chance that it expires worthless (and you keep all the premium).

So when I say “sell a 30-delta put option,” that means go to your options chain, find an available put contract with a delta close to 0.30, and sell it. A 30-delta put has roughly a 70% chance of expiring worthless, which is exactly what we want as Wheel traders, because our goal is to keep 100% of the premium received.

Note: For puts, delta is always shown as a negative number. In the AMD example above, you can see that the 30-delta put corresponds to the $160 strike contract.

So, we want to be selling OTM put contracts with a delta of around 30. Why 30? Because it gives us about a 70% probability that the option will expire worthless, which is exactly what we want. But why not sell a 10-delta put and get an even higher, 90% probability? Because the juice isn’t worth the squeeze. The further OTM you go, the less premium you collect, since the likelihood of that option expiring worthless is already very high.

There’s a sweet spot when selling options, a balance between odds and profit. Most research suggests the optimal range is between 20–30 delta. For our strategy, we’ll stick with a consistent 30-delta put when selling.

Delta conclusion: Sell a 30 delta put contract.

Theta:

Theta, also known as “theta decay” (and also the name of my brand, business, logo, whatever you want to call it), is my favourite option Greek. It holds a special place in my heart. I’m a mathematics student, and we tend to form strange relationships with numbers and variables, weird, I know.

Let me explain Theta in a slightly romantic way: Theta measures how much an option contract loses in value purely from the passage of time. Every option is marching toward a fixed point in time, think of it as the singularity. The option can never escape; time only moves forward. And as the option approaches expiration, its time value decays faster and faster, until the contract either expires worthless or finishes ITM. But the extrinsic value of the option will always decay to $0 at expiration, and at this point you'll either end up with a delta of 1 or -1.

Because we’re short options, that makes us long Theta, and a long Theta position means we profit from the passage of time. In other words, we’re literally selling time. How cool is that?

This naturally leads to the correct assumption: if there’s more time until expiration, there’s a longer window for the option to finish in the money. Therefore, the more time left, the more expensive the contract. And you’d be right.

So time is baked into the options price.

What's the best time till expiration for option sellers?

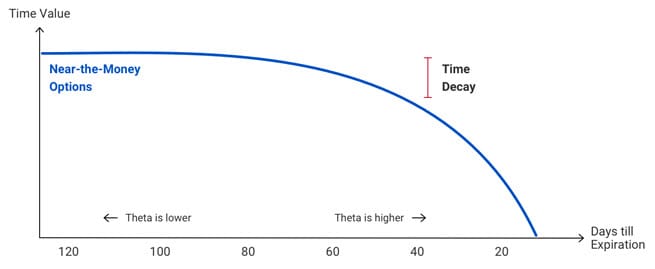

From here on out we will go by DTE (Days Till Expiration), for example 20 DTE simply means "20 days until the option contract expires". To answer the question, we will refer to the theta decay graph below:

As you can see, time decay isn’t linear, it’s exponential. This means an option’s value decays faster as expiration approaches. As an option seller, your goal is for the option contract to lose as much value as possible (remember we are short that contract, so we want the price of that contract to go down), so we want fast Theta decay working in our favour.

Looking at the graph above, Theta decay doesn’t help us much between 120 and 80 days to expiration (DTE), as the rate of decay remains relatively flat. The curve really starts to drop off after about 60 DTE.

It’s generally good practice to sell options around 45 to 30 DTE. In my opinion, it doesn’t make a huge difference either way, shorter DTE means faster Wheel cycles and quicker turnover, but smaller premiums per trade. Longer DTE gives you larger premiums, but slower turnover. It’s all mostly priced in, so in the end, it comes down to personal preference. For this strategy, we’ll stick with 30–45 DTE for every contract on the short put side of the wheel.

Theta conclusion: Sell a put contract with 30-45 DTE

Implied Volatility:

Explaining IV (Implied Volatility) in its true, technical sense can be a little tricky to wrap your head around. So, to make it simple, I’ll explain it in two ways, first the formal (textbook) definition, and then the street version that actually makes sense in the real world.

Textbook definition of IV:

Implied volatility is the market’s forecast of the likely magnitude of future price movements in the underlying asset, expressed as an annualized percentage. It is derived from an option’s market price using an option pricing model (such as Black–Scholes) and represents the volatility level that, when input into the model, yields the observed market price of the option.

Street definition of IV:

Just think of an insurance company that sells car insurance. When you buy car insurance, you pay a premium, usually monthly (whereas in options, it’s a one-off payment) to insure your vehicle. How does the insurance company decide how much to charge you? They look at your driving history (among other factors). If your driving history is volatile, meaning you’ve had numerous accidents, they’ll charge you higher premiums.

The same concept applies to options pricing. The more volatile a stock is, the higher the premiums you’ll pay (or collect, if you’re the option seller). Think about it, it makes perfect sense. The likelihood of a long option position becoming profitable increases when the stock experiences larger price swings, because it’s statistically easier for the underlying stock to reach your strike price. Therefore, it makes sense to charge more for a volatile stock, and less for a stable one.

How is IV measured?

Implied Volatility (IV) is the options market’s forecast of how much the underlying stock might move over the next year.

For example, if you see an IV of 50%, it means the market expects the stock’s price to stay within roughly ±50% of its current value over a one-year period. It doesn’t predict direction, only the expected magnitude of price movement.

From IV alone, you can get a sense of whether an option’s price is expensive or cheap. However, using the raw IV number by itself can be misleading. For example, a 100% IV on one stock versus a 50% IV on another doesn’t automatically tell you which option is expensive, because each stock has its own normal volatility range.

Think about it: if Stock A is GME (GameStop) and Stock B is AAPL (Apple), GME will almost always have a higher IV than Apple, even when GME’s IV is actually cheap relative to its own historical levels.

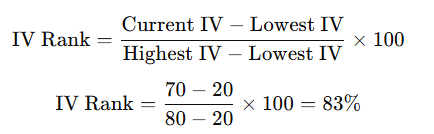

To solve this problem, traders use something called IV Rank.

IV Rank

IV Rank measures where the current implied volatility sits compared to its range over the past year. It tells you whether IV is high or low relative to its own history, helping you decide if options are expensive or cheap for that specific stock.

Let’s say a stock’s implied volatility (IV) has ranged from 20% to 80% over the past year, and its current IV is 70%.

To calculate IV Rank, you measure where the current IV sits within that 1-year range:

So, this stock’s IV Rank is 83%, meaning current volatility is near the top of its yearly range, options are relatively expensive.

If IV were sitting near 25%, that would give an IV Rank of about 8%, meaning options are cheap compared to their historical volatility.

For us, IV Rank is worth noting, but since we’ll be trading the Wheel in a systematic way, it doesn’t matter too much. You’ll often notice IV increasing around earnings season, which can be a great time to sell options because premiums are higher. But remember, you’re getting paid to take on that extra risk, and earnings can cause violent price swings.

However, since we’re wheeling stocks that we’d be happy to own anyway, this risk is acceptable. In fact, if possible, I’d recommend trying to time your option sales around earnings to take advantage of those inflated premiums.

The last thing I’ll say about IV is that, generally speaking, IV is too high, meaning options are often overpriced. That might sound like a throwaway comment, but it’s actually a well-researched fact. There are thousands of academic papers and books analysing how options, on average, tend to be overpriced.

The main reason is that, as I mentioned earlier, selling options is a lot like selling insurance, and the seller of insurance must always be compensated for taking on risk. Knowing this, we use it to our advantage by being net sellers of options. To protect ourselves from the rare but inevitable tail risks that come with option selling, we hedge using either cash or stock ownership, both of which are built into the Wheel strategy.

IV Conclusion: Implied Volatility is something worth keeping an eye on, but since we trade the Wheel in a systematic, rule-based way, there’s no need to overthink it.

Step 1: Selling a put contract - summary

Sell an OTM put contract between 30-45 DTE with delta of about 30. IV, you can look out for, perhaps try and sell when IV is high (generally around earnings) but don't overthink it, stick with the plan.

Step 2: Get Assigned

Since we’ve already covered Delta, Theta, and IV in Step 1, the bulk of the learning is done. The rest is the same, but slightly different. This next step is much simpler.

What do you mean "Get assigned?"

It’s in the title, we basically sit back and wait to get assigned. Because we’re selling put contracts, our goal is to avoid assignment for as long as possible.

Let’s say we consistently sell 30 DTE puts and do nothing until expiration. If the underlying stock price never drops below our strike (which is what we want), the contract will expire worthless, and we’ll collect 100% of the premium each time.

Now imagine this happens five times in a row, that’s five 30-day cycles, or about 150 days of pure premium collection. A great outcome.

But eventually, things won’t go our way, and that’s completely expected. We’re professionals with a plan, not panic sellers. So what do we do when the underlying stock falls below our strike price and we get assigned?

Simple, we do nothing. We sit back and let assignment happen. The next trading day, you’ll wake up to find 100 shares (or multiples of 100 if you sold more than one contract) sitting in your brokerage account.

Congratulations, you now own stock in a company you wanted to own anyway.

And that’s the key part: if it’s a company you truly like, why would you be upset about finally owning it?

Now, the most important part of this step, aside from making sure it’s a company you actually want to own, is ensuring you have enough available cash in your brokerage account when assignment day finally arrives. You need to be ready to buy 100 shares of the underlying stock at the agreed-upon strike price when the contract is exercised.

FYI - this part of the Wheel is actually a strategy in itself, known as a Cash-Secured Put (CSP).

Step 2: Get Assigned - Summary

Make sure it’s a stock you genuinely want to own, and ensure you have enough available funds in your brokerage account to purchase the assigned shares when the day comes.

Step 3 : Sell a call contract against those shares

Congratulations! You now own 100 shares of a company you already wanted to own, and you even got paid to take the position. Pretty sweet, right? You literally got paid to buy a stock you liked.

So, what’s next? The money machine doesn’t stop there. Now that you own the shares, you can start selling call contracts against your position. Since you already own the stock, you’re 100% hedged against the tail risk of selling those calls, that risk is fully covered.

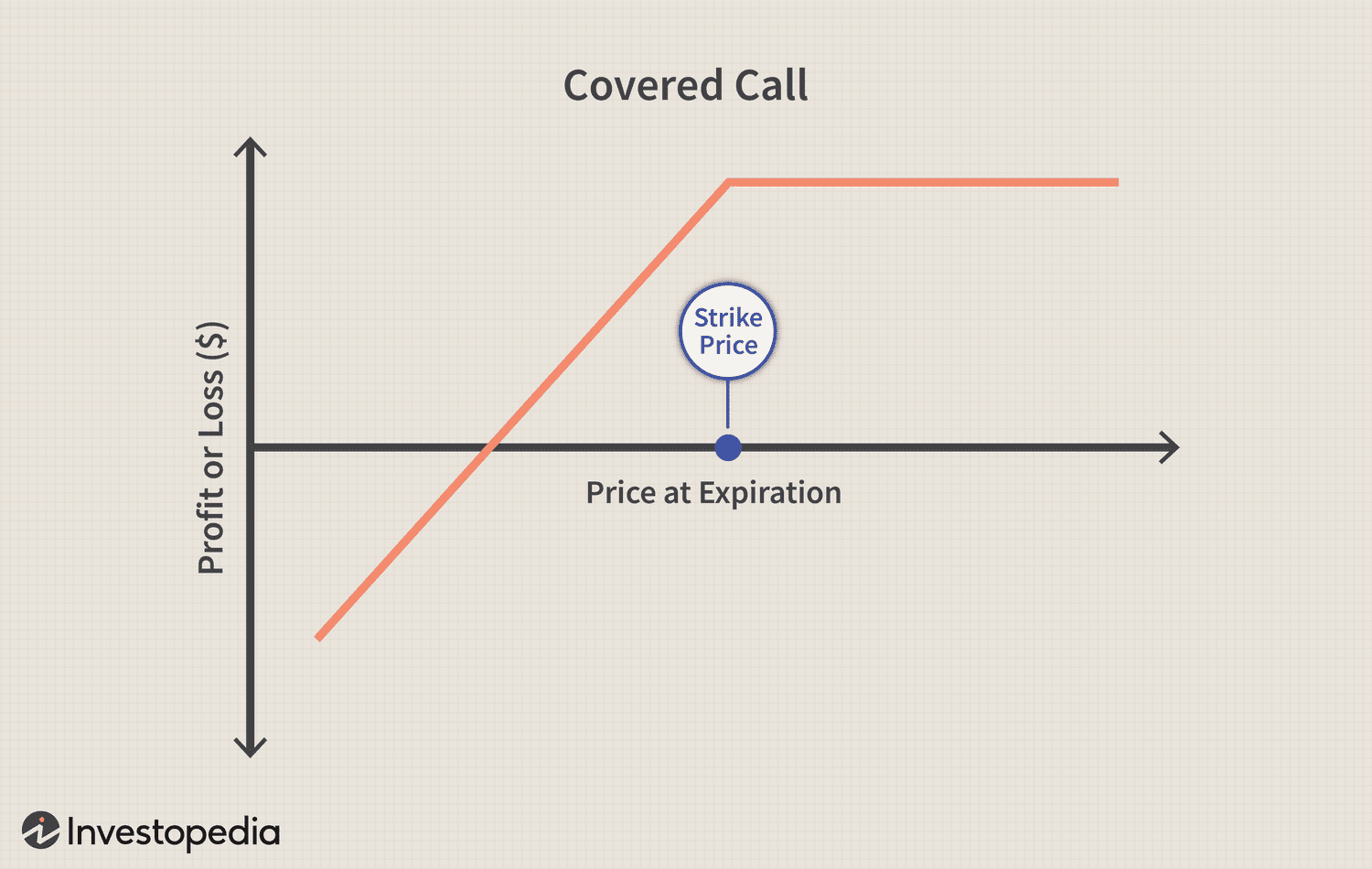

This part of the Wheel is actually its own standalone strategy, known as a Covered Call (CC).

Selling a call contract has the opposite effect of selling a put contract. Remember, when you sell a put and get assigned, you’re obligated to buy 100 shares at the agreed-upon strike price. With a call contract, it’s the reverse, if you get assigned, you’re obligated to sell 100 shares at the strike price.

If you were naked (meaning you don’t own the underlying shares), you’d end up being short 100 shares, which exposes you to theoretically unlimited losses if the stock price keeps rising. This is especially risky because most options expire after market close on Fridays, meaning you could technically be short a stock over the weekend, completely exposed to price gaps or major news events before Monday’s open. Luckily for us, we are hedge because we won the underlying stock, so if that does happened, its our underlying stock that would get called away, and we would be square again.

The trade

The Covered Call (CC) trade is very similar to the Cash-Secured Put (CSP) we covered in Step 1. For example, we sell a 30–45 DTE call contract with a 30 delta, sound familiar? The “selling the contract” part is almost identical, and you’ll earn similar premiums too.

But here’s the cool difference: not only do you get paid for selling the option, you can also make capital gains as the stock price rises, remember, you still own those 100 shares. This means you now have two income streams: premium income from selling calls and potential price appreciation from the stock itself.

If the stock price finishes above your strike price at expiration, you keep 100% of the premium received plus the capital gains up to the strike price.

For example, if the stock was trading at $100 when you sold the call with a $120 strike, and at expiration the stock finished at $150, you’d keep the $20 per share gain (from $100 to $120), plus the premium received.

The only thing you miss out on are the gains beyond your strike price, but that’s the trade-off for earning consistent income.

Just like with the CSP (Cash-Secured Put) position, you’ll keep selling 30-delta calls with 30–45 DTE again and again until you eventually get called away (meaning the 100 shares you own are sold). Maybe you get through five cycles, that’s five rounds of premium collected, or maybe you get called away on the very first one. It doesn’t really matter.

Getting called away represents the maximum profit potential for the covered call trade, and it simply means you get to restart the Wheel cycle (back to selling puts). If you don’t get called away, no problem, you just roll right into selling another call and keep the income flowing.

Step 3 : Sell a call contract against those shares - Summary

Repeatedly sell 30-delta, 30–45 DTE call contracts against the 100 shares you own until you get called away.

Step 4: Your shares get called away.

Once you get assigned (meaning the stock price finishes above your call’s strike price at expiration), the 100 shares you owned from the CSP trade will be automatically sold. This process is called “getting called away”, which simply means your shares were sold.

At that point, you’re back to square one, you no longer own any shares, and you’re not short any contracts. You’re completely neutral again.

So, do nothing, let yourself get called away, and then repeat the cycle, back to selling puts.

Step 4: Your shares get called away - Summary

Do nothing, let yourself get called away.

Step 5: Repeat the cycle

To quote True Detective, “You’ll do this again, time is a flat circle...”

After getting called away, rinse and repeat. Congratulations, you’ve just completed your first full revolution around the Wheel. Now get back on that horse, return to Step 1, and start the process again by selling 30-delta, 30–45 DTE put contracts.

This completes all five steps of the Wheel Strategy. If you’ve made it this far, congratulations! You now know how to trade the Wheel. But keep reading, because next we’ll dive into some critical factors to consider while trading the Wheel, things that can make or break your strategy.

Step 5: Repeat the cycle - Summary

Simply repeat the process by rolling straight back into Step 1 - selling 30-delta, 30–45 DTE put contracts.

What's the catch?

So far, the Wheel Strategy sounds too good to be true, right? It almost feels like you win in every scenario. Well, let’s take a closer look and see when you actually lose, and what the main risk really is.

Here are the possible outcomes for the underlying stock:

- Up big: Profit

- Up small: Profit

- Flat: Profit

- Down small: Profit

- Down big: Loss

So, our main risk is that the underlying stock experiences a major drop. The loss would have to exceed the total premium received from selling options. Interestingly, if you’ve been wheeling a stock long enough, it’s possible for this risk to cancel out over time, meaning the total premiums collected could eventually outgrow the total value at risk (for example, if you owned 100 shares and the stock went to zero). It would take a long time, but it’s still a possibility.

Put simply, your risk profile is similar to that of holding long stock, since both the CSP and CC positions are bullish trades. They profit from an increasing share price, a flat share price, or even a small decline that doesn’t breach your strike price. In fact, your risk profile is slightly better than being long stock, because the premium received effectively lowers your breakeven point on the position.

For example, if you were long AMD and over the course of three years the stock price dropped by 50%, doing nothing would leave you down 50%. But if you had been wheeling the entire way down, the premiums collected would help cushion that loss, or potentially even offset it completely.

However, one important drawback to note is the missed upside opportunity. Because you’re always either short a put or short a covered call, your upside is capped compared to simply holding the stock long.

This brings us to the next key section, finding suitable underlying stocks for the Wheel strategy.

Finding Suitable Underlying Stocks to Wheel

We have a few key items on our checklist for potential Wheel candidates. These help us filter out risky plays and focus on reliable, premium-generating stocks:

- A bullish outlook on the stock - You want to be confident the stock will hold or rise over time.

- Not too bullish - Being overly bullish can lead to missed upside if your shares get called away. It’s more of an annoyance than a disaster, but still something to note.

- Strong, established companies - Stick with quality blue-chip names that have consistent performance and solid fundamentals.

- Avoid bankruptcy risk - Stay away from companies with financial instability or a high chance of severe drawdowns.

- Good option liquidity - Choose stocks with tight bid/ask spreads and active option chains to ensure smooth trade execution.

A hurdle you’ll quickly discover with this strategy is the cash required to run it. While the Wheel can still be done with a smaller account, it often means restricting yourself to cheaper or riskier stocks (which, full disclosure, is exactly what I’m about to do lol, more on that shortly).

The reason is simple: you need enough available funds to buy 100 shares of the underlying stock if you get assigned. Using AMD as an example, with the stock currently trading at $164 per share, you’d need $16,400 USD in your brokerage account to run the Wheel on it (or roughly $4,000–$8,000 if you’re comfortable trading on margin). And as you’ll notice, most solid U.S. stocks trade in the hundreds of dollars per share.

There’s no direct correlation between a lower share price and a riskier stock, but in practice, it often works out that way, big, stable, blue-chip stocks (the best Wheel candidates) usually trade at higher prices.

To keep things simple, I’ll make the underlying stock selection process short and sweet by using a professional options screener I use (and pay for), and I’ll share the results with you.

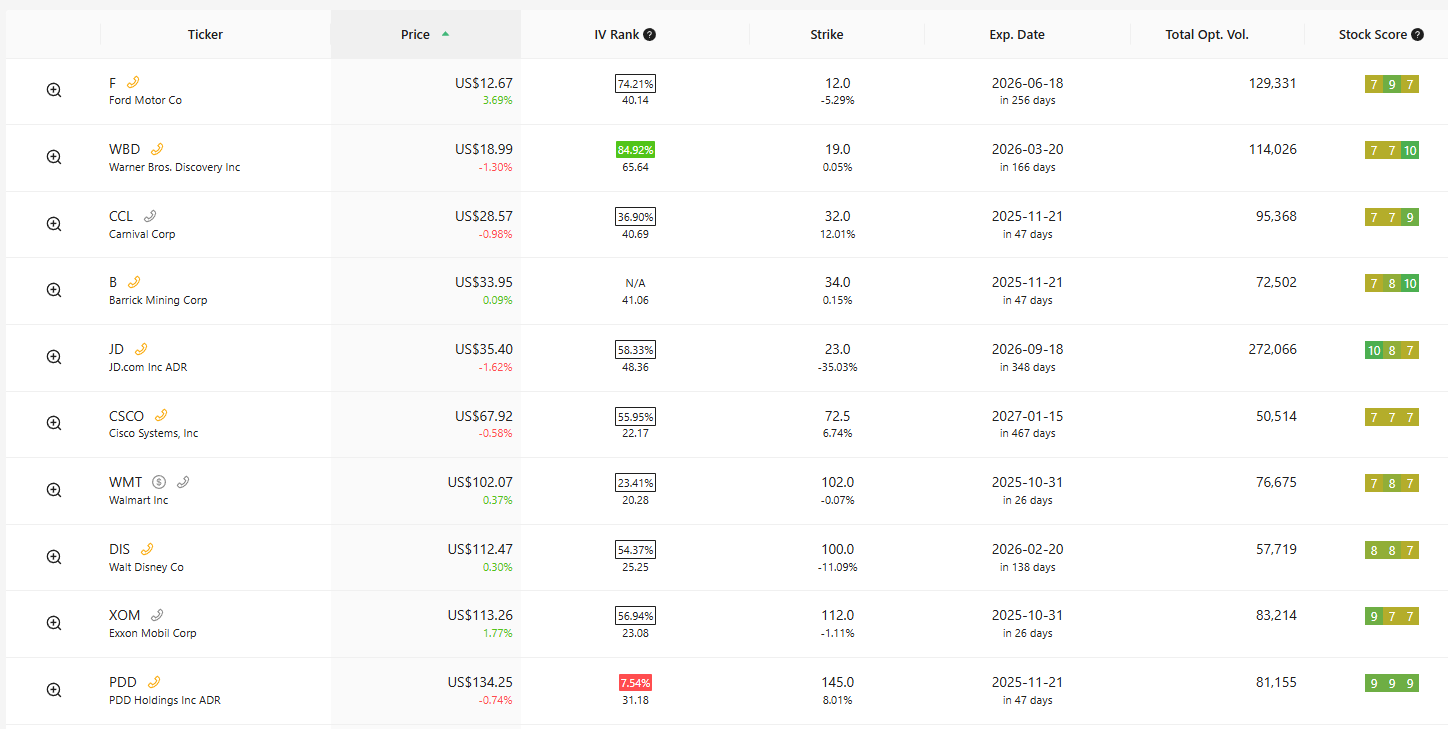

Ignore Strike, exp.date and IV rank on the above screenshot as its irrelevant in this context.

The screenshot above if from some filters I have set on an option screener. the filters are, Stock scores above 7 (10 being max) for fundamental, growth and technical. Total option volume of above 50,000 and have filtered via cheapest share price to most expensive.

As you can see, these are all solid, recognizable companies - Ford, Warner Bros., Barrick Gold, JD.com, Walmart, Disney, ExxonMobil, and others. All are stocks I’d feel comfortable wheeling.

For example, you could start wheeling Ford with as little as $1,267 USD in your account.

If you have more available funds, wheeling larger names like Walmart, NVIDIA, Apple, or AMD would be ideal. These companies aren’t going anywhere anytime soon, and they carry enough market interest and volume to maintain healthy implied volatility (IV), which means richer option premiums when selling contracts.

When it comes to “what stock should I wheel,” the rule of thumb is simple, stick with good, solid companies, the kind of names everyone knows and trusts. If you do that, you really can’t go wrong.

Now, this is the part where I break my own rules, because I’m crack addict for premium and can’t help myself. While writing this, I looked at Ford, a solid company, no doubt, but because it’s stable, the option premiums just aren’t that exciting. For example, with a $1,500 account, I could sell one 30-delta, 33-DTE put contract on Ford and collect about $24 in premium.

Or… I could sell two 30-delta, 33-DTE put contracts on Snapchat (SNAP) and collect about $140 in premium, that’s 5.8x more than Ford would pay.

Of course, that extra juice comes with extra risk. Snapchat is, frankly, a terrible company, its balance sheet is a war zone, and it’s been bleeding cash since inception without ever turning a profit. That’s the sketchy nature of this trade.

Still, after around 12 successful Wheel cycles on SNAP (assuming $140 per cycle for two contracts), I’d have earned more in premium than my maximum possible loss if the stock price went all the way to zero.

Please don’t try this at home (unless you are comfortable with the risk). Stick to solid companies when running the Wheel. My decision to wheel Snapchat (SNAP) is purely for demonstration purposes, to show the full ins and outs of the strategy, and probably even the worst-case scenario of wheeling something as sketchy as SNAP.

That said, Snapchat does still have around 500 million daily users, so I don’t believe the company is on the verge of bankruptcy, though the risk is definitely still there. There’s a real chance management could eventually turn things around, but for now, it’s far from a sure bet.

Anyway, for me, it’s wheeling Snapchat. And if you’ve been following my Slush Fund Portfolio (money I am willing to lose) updates, you already know I don’t exactly have spare cash lying around anyway (lol). At least this will be fun and I’ll document the ups and downs of the process in real time. From here on out, I’ll be using Snapchat as my live demonstration for this Wheel strategy.

Tracking Your Progress

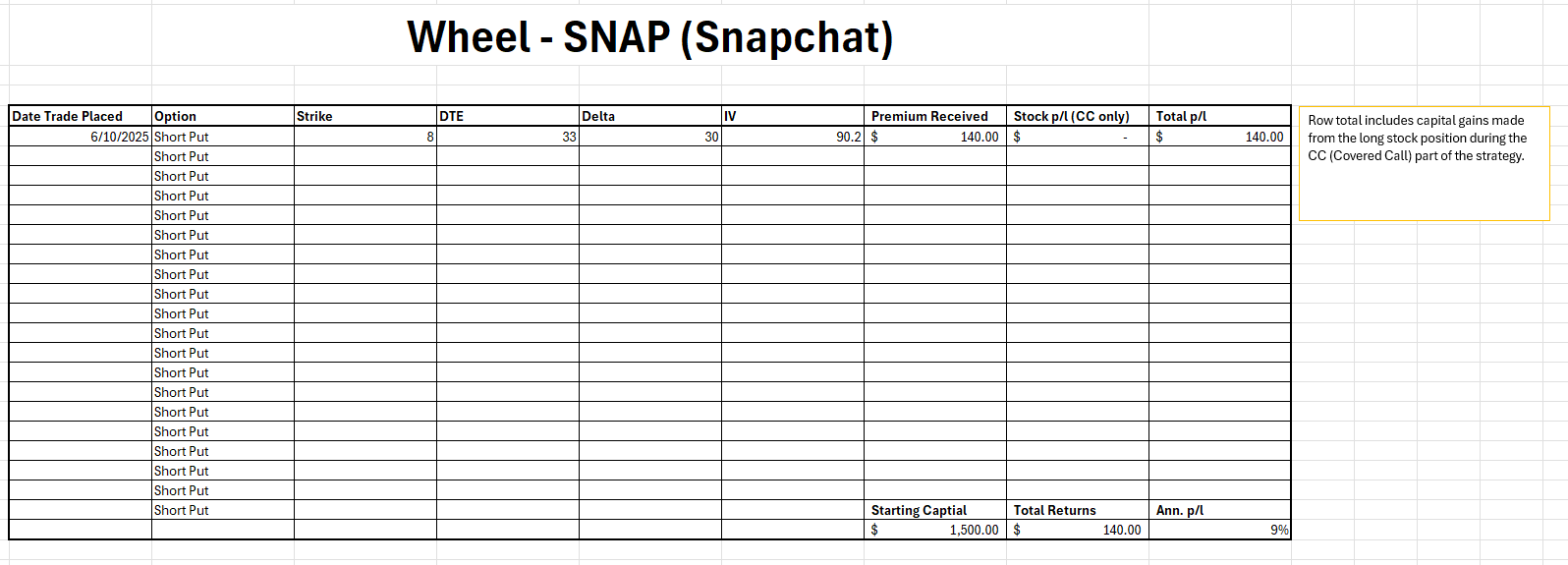

It’s important to track your progress for each Wheel you have running. Since you may get assigned and called away multiple times, you need to keep an accurate record of the overall P&L (profit and loss) for each individual Wheel cycle.

To make this easier, I’ll provide a free basic Excel spreadsheet below that you can use to track your trades and monitor your results.

The Wheel Logbook Spreadsheet looks like the screenshot above, it’s pretty basic, but it’s all you need. Your brokerage platform will provide the rest of the data.

It’s also a great way to collect performance data and observe which Deltas, DTEs, and IV levels performed best, allowing you to make informed adjustments in the future.

I’ve set it up using Snapchat as an example, but feel free to customize it for whatever stock you’re trading. If you’re wheeling multiple stocks, simply copy the sheet, create a new tab, and rename the tab and titles accordingly.

Final summary

Step One: Find a viable stock to wheel and sell 30-delta, 30–45 DTE put contracts.

Step Two: Continue selling put contracts until you get assigned.

Step Three: Once assigned, you’ll hold 100 shares per contract sold of the underlying stock.

Step Four: Sell 30-delta, 30–45 DTE call contracts against your shares.

Step Five: Once called away, return to Step One and repeat the cycle.

Most people go wrong when trading systematically because they don’t follow their own rules. No matter what’s happening with the underlying stock, stand firm, don’t waver from your plan, and continue executing your strategy systematically.

If you find yourself feeling scared or stressed, you’re probably trading with too much money or taking on too much risk. A good test is simple: are you sleeping well at night? If not, scale down. There’s no such thing as a risk-free strategy, and most of the time, you are your own biggest risk. So if you go down this path, trust the process, stay disciplined, and it will work out over time.

Returns on the Wheel strategy can vary, I’ve seen results as high as 70% annually, and others closer to 20%. Both are great, especially considering the market average is around 8%. Just remember: the Wheel will likely perform about as well as the market during a downturn too, everyone looks good in a bull market.

My overall advice: the Wheel is a great strategy that deserves a place in your portfolio alongside other positions. And honestly, it’s also a lot of fun to trade.

From here, I’ll be providing regular updates on my Snapchat (SNAP) Wheel. I’ll post all future updates below as the strategy unfolds.

Final Thoughts:

I like the strategy

If you found value in this Wheel DD, feel free to leave a tip, or come back and donate if the strategy makes you a profit. Every contribution, big or small, helps keep these reports coming and motivates me to keep digging deeper.

SNAP (snapchat) Wheel Strategy progress Update

In this video, I go through a live trade, and go over step 1 - Selling a put contract in real time. Skip to 17:50 if you only want to watch this part.